The Reach for Kalaallit Nunaat – A Matter of Scale?

An inquiry into how Greenland is seen, sized, and claimed through maps – and how other forms of cartography resist that reduction.

Greenland as a Cartographic Object

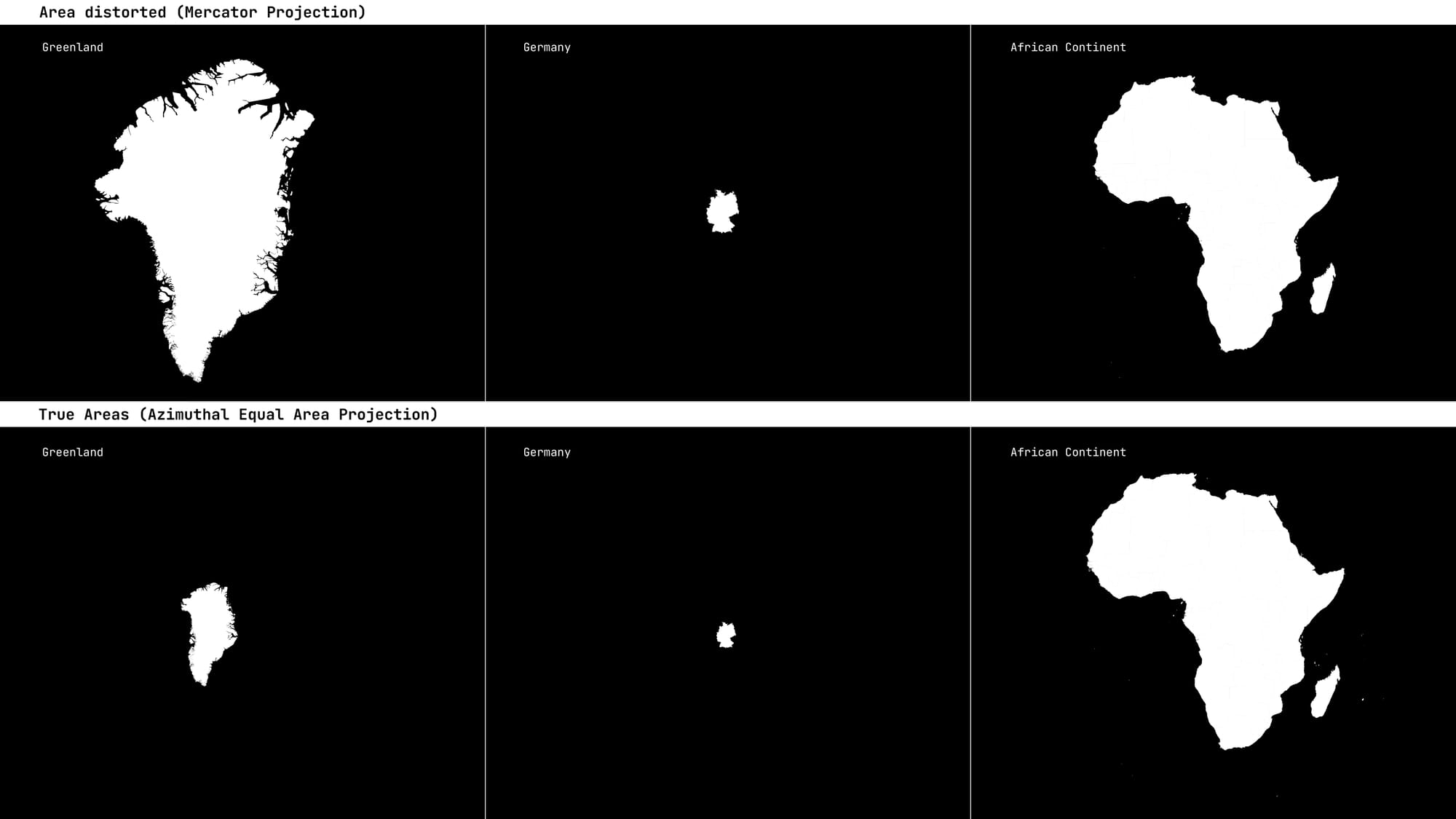

When I started Re:connaissance, I pledged myself a vow: I would never write an essay about the area distortions of the Mercator projection. The topic has been rehearsed endlessly; not only by cartographers, information designers or other experts, many major news outlets return to it every few years. By now, I thought, we all know that Greenland is not larger than the African continent, that Europe does not dwarf South America, that the sizes of world areas are not true the way the Mercator projection suggests.

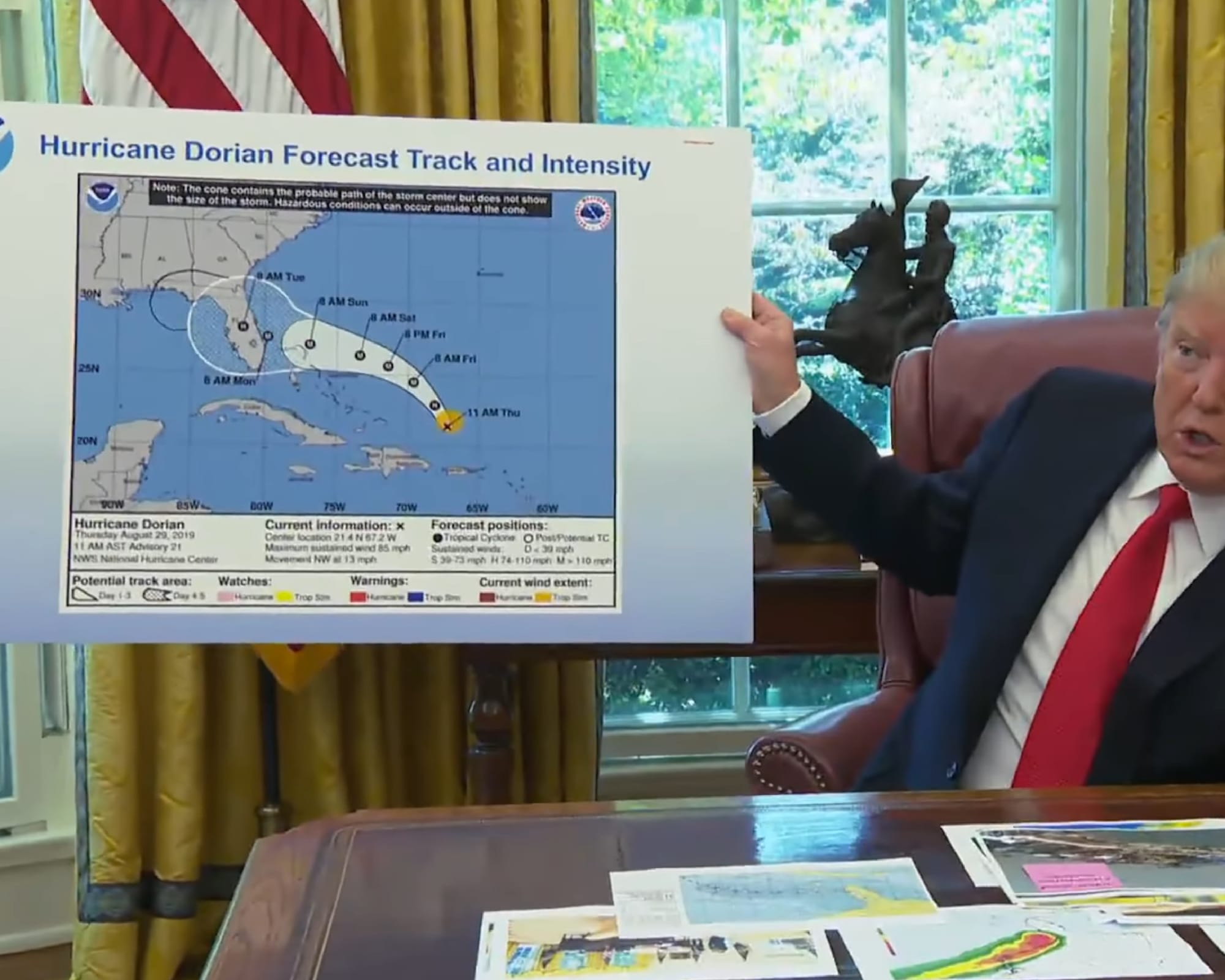

This vow, however, did not account for the 47th sitting president of the United States of America. We already know that while Donald Trump has a particular fondness for maps as powerful political images (in early 2025, he renamed the Gulf of Mexico to Gulf of America) – and for design more generally as a convenient tool of propaganda (he signed Executive Order 144338 which then led to a National Design Office »America by Design«) – his diagrammatic understanding, or visual literacy, is at best limited. In 2017, during what later became known as Sharpiegate, the president publicly altered the projected path of Hurricane Dorian – the so-called cone of uncertainty – by drawing over it with a black marker. The modified map created confusion at best, and at worst undermined trust in critical emergency information.

From left to right | top to bottom: Fig 1: Map of the »Gulf of America« in the White House. Fig 2: Trump presenting the Hurricane Cone including its Modifications with a Sharpie in his first Term. Fig 3: Trump signing Executive Orders.

And then there is Greenland – or rather, Kalaallit Nunaat, its original name.

The United States already enjoys near-total military and strategic access to Greenland through long-standing agreements with Denmark. Economically, too, there is little standing in the way: American companies are free to invest in infrastructure, resource extraction, and research, and have done so repeatedly.

Against this background, media and political observers around the world are puzzled why Trump’s cost-benefit calculation insists on ownership of Greenland; possession would not meaningfully alter American power on the island.

I love maps. And I always said, ‘Look at the size of this, it’s massive, and that should be part of the United States.« – Donald Trump, 2021

A simple explanation might be:

Trump’s interest in acquiring Greenland was never primarily strategic. It was real estate. As he explained in an interview by The New Yorker magazine in 2021, ‘Why don’t we have that?’ You take a look at a map. So I’m in real estate. I look at a corner, I say, ‘I gotta get that store for the building that I’m building,’ et cetera. You know, it’s not that different. I love maps. And I always said, ‘Look at the size of this, it’s massive, and that should be part of the United States.’ ”

One cannot help but wonder whether this obsession was formed in front of a Mercator map – where Greenland appears, indeed, massive?

Beyond Greenland's Static Surface Area

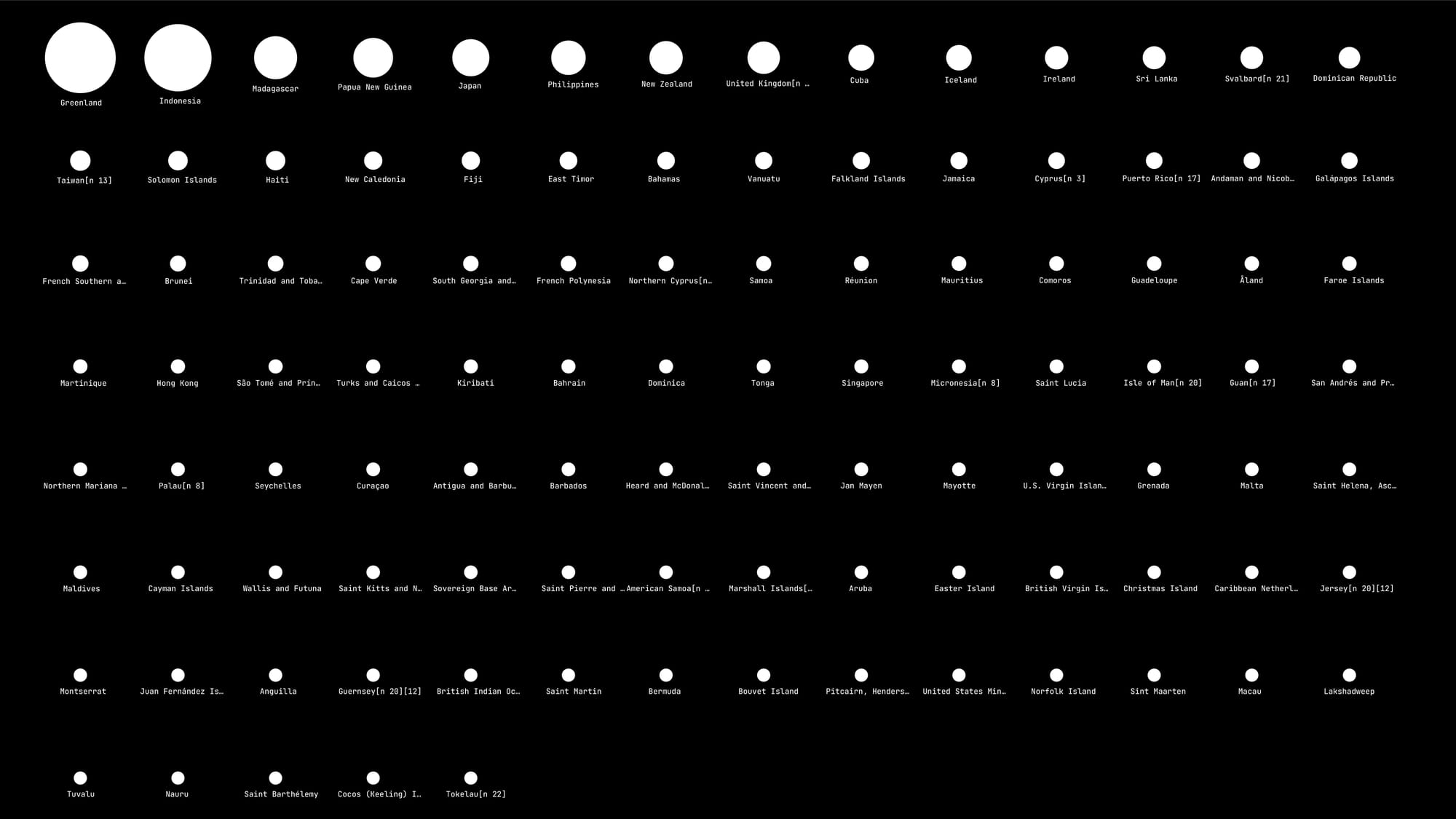

Would a different projection have produced a truer area size —and with it, a different political desire? Indeed, among the 105 islands defined as countries or territories worldwide, Greenland is the largest – closely followed by Indonesia.

An island is an area of land surrounded by water on all sides that is distinct from a continent. Continents have an accepted geological definition – they are the largest landmass of a particular tectonic plate. Islands can occur in any body of water, including lakes, rivers, seas.

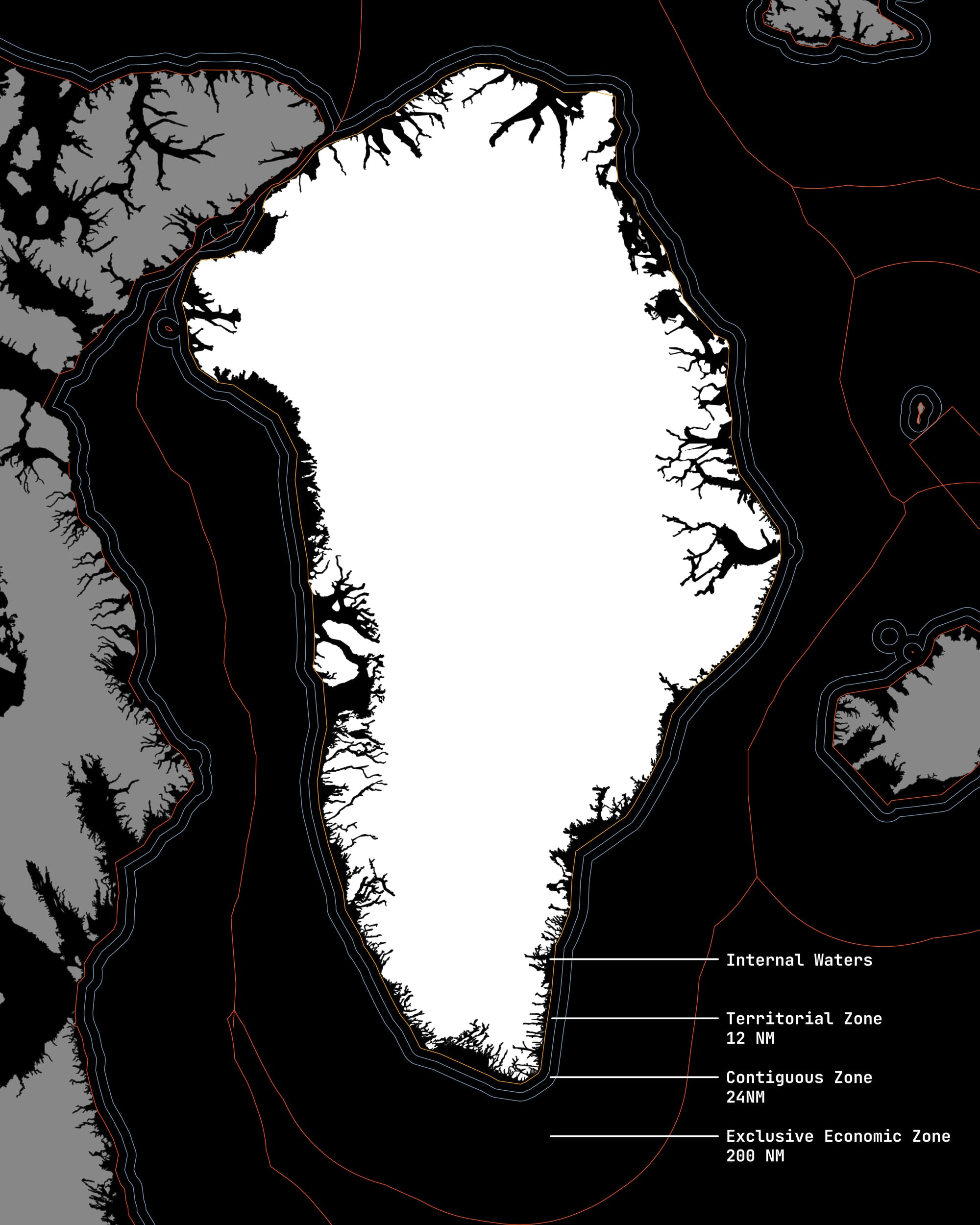

Compared to land-locked states or territories, islands are governed by a different legal framework with a more complex border apparatus. Bounded on all sides by the sea Greenland’s effective borders extend outward through a layered system of maritime zones measured in nautical miles (1 NM = 1.852 km): Internal Waters, Territorial Waters (12 NM), Contiguous Zone (24 NM) and finally the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ, 200 NM).

Each of these zones carries different legal implications. Within the EEZ, for example, the adjacent state has sovereign rights to explore and exploit both living and non-living resources. In this sense, Greenland’s significance is not contained within its surface area; it unfolds into its surrounding waters, which rarely appear on world maps.

Fig 1: Greenland and its Maritime Zones. Fig 2: Greenland where the Exclusive Economic Zone is visualized as Size. ©Robin Coenen. Data: Marine Regions Org

These surrounding waters are especially significant in Greenland’s case because what appears static on common maps is anything but. The Greenland Ice Sheet –the second largest body of ice on Earth after Antarctica – is losing mass at accelerating rates due to climate change. This loss alters not only elevation and reflectivity, but also access: to seabed resources, to newly navigable waters, and to seasonal shipping routes. As sea ice retreats, particularly during summer months, the Arctic shifts from a frozen barrier to a dynamic space of movement, activating geopolitical interests once constrained by permanent ice.

Flags on Maps

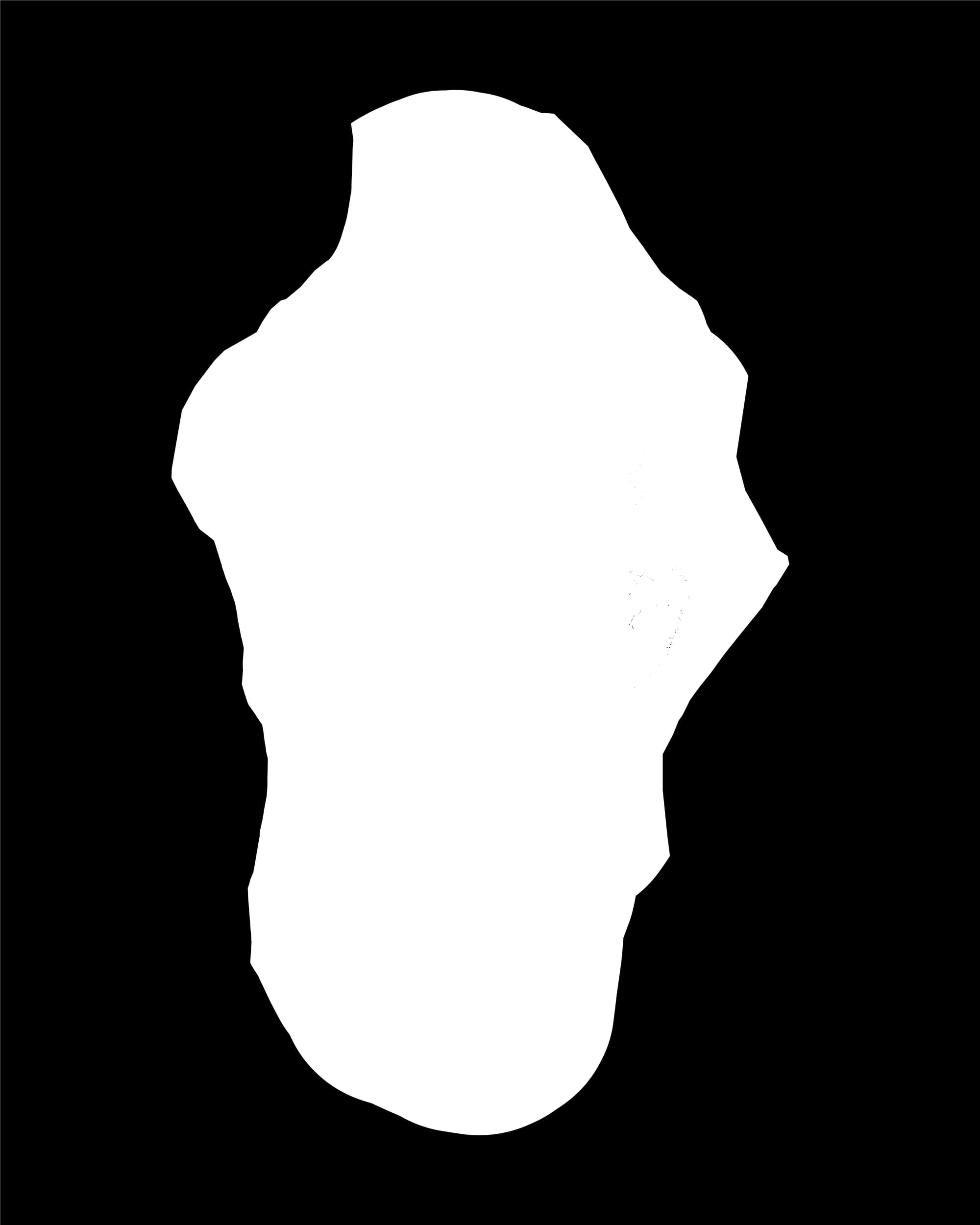

In the 2020s, amid renewed territorial rhetoric and media narratives announcing a return to the law of the strongest, one of the oldest cartographic gestures of power seems to reappear: the flag placed on a map; An act of the most direct visual expressions of territorial power. It is a gesture that precedes law, administration, and often even physical presence. Historically, this practice accompanied European imperial expansion, where vast regions – frequently marked as »terra incognita« – were symbolically occupied sometimes long before any form of (colonial) governance existed on the ground.

In contemporary political imagery, this gesture persists with remarkable simplicity. Maps circulate on social media showing entire regions overlaid with national symbols, sometimes accompanied by short captions or slogans. The complexity of geography, population, culture and law is displaced by a single visual act. In this process, the map is reduced to what Benedict Anderson described as a logo-map (Logokarte): a cartographic surface stripped of geographic content and context, transformed into a pure sign.

A Different Approach to Cartography

The close association between Greenland and the Mercator projection has hardened into a cartographic shorthand and leaves a larger history unseen: Greenland has been mapped in many other ways, for very different purposes.

Against the god-view of modern cartography – what Donna Haraway described as the illusion of seeing everything from nowhere – Inuit cartographies of Kalaallit Nunaat articulate a fundamentally different understanding of what a map can be. These maps were not conceived as representations to be surveyed from above, but as artefacts designed for use: to be held, handled, and activated through touch.

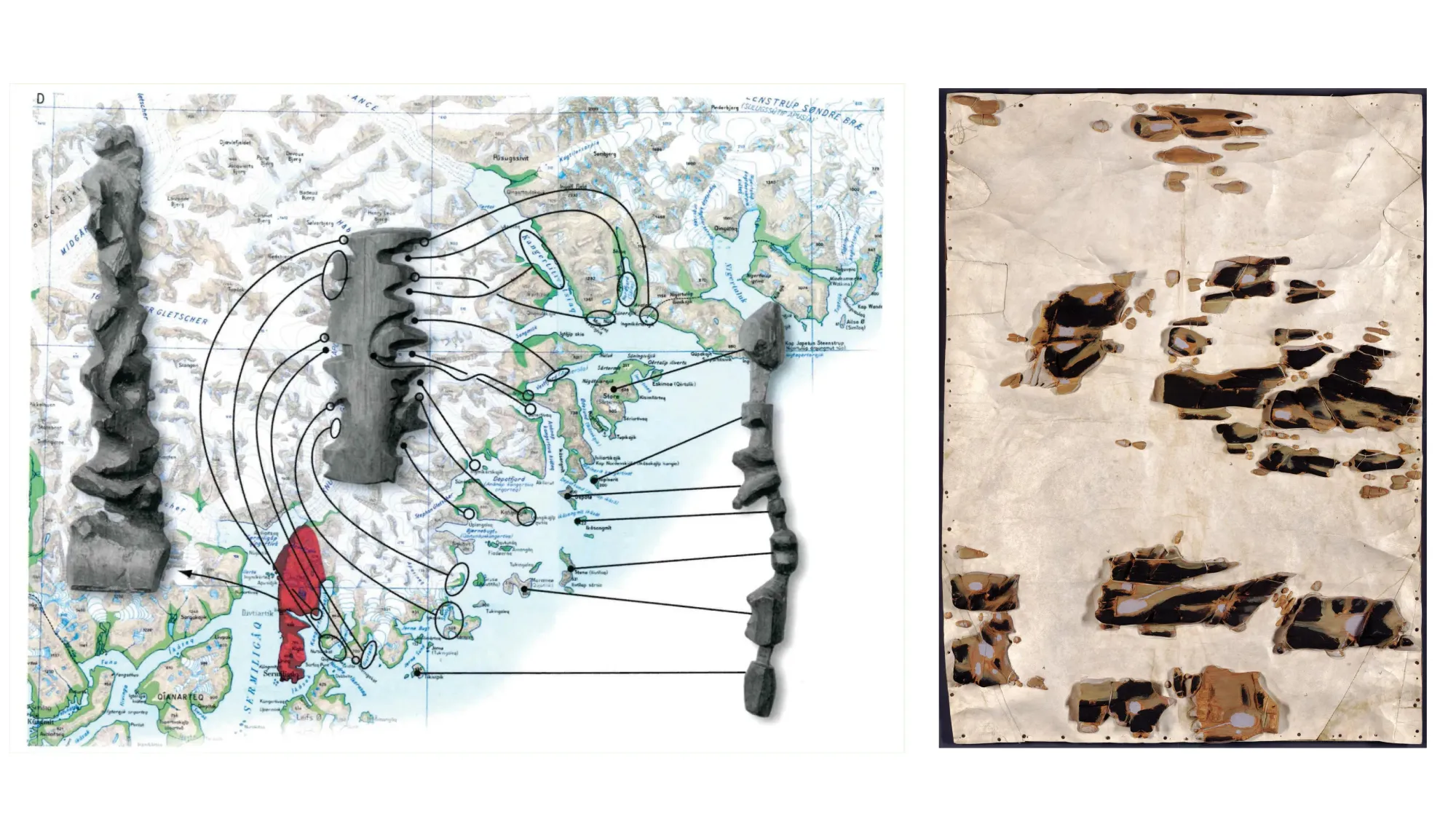

Their materiality extended well beyond the flat surface of paper. Coastlines were carved from driftwood, shaped to fit the hand and assembled into composite forms. In one commissioned map, individual islands were produced from Siberian driftwood and sewn onto a base of sealskin. The surface was then painted to encode environmental knowledge: yellow marking grassy and swampy land, blue indicating lakes, black denoting areas covered by lichen, while tidal zones were left uncoloured and reefs lightly traced in pencil. Rather than abstracting space, the map gathered terrain, material, and memory into a single object.

Used alongside oral narration, such maps functioned less as static records than as prompts for explanation and rehearsal. Coastlines were traced by hand as routes were described, hazards recalled, and journeys imagined.

These cartographies followed a perspectival and tactile logic. Space was not presented as an image (or territory) to be mastered at a glance, but as a series of movements and encounters—knowledge that could be grasped, quite literally, in the hand.

Here, mapping is not a claim to space, but a way of being in it.