Bending Time: Retracing Timezones Off Lines — Sight Regimes II

Examining the lines — and absences of lines — of timezones on the World map raises intriguing questions: From China’s single timezone to Franco’s timeshift. This second essay in the Series SIGHT REGIMES explores time zones as political and cultural operations.

»The clock, not the steam-engine, is the key-machine of the modern industrial age.«

— Lewis Mumford, technics and civilization, 1934

The clock, Lewis Mumford once remarked, was the true machine of the modern age. Not the steam engine, not the spinning jenny, but the quiet, repetitive mechanism that detached hours from the sun and bound them to the always-turning gears of steel instead. With the invention of this mechanical time, the rhythm of human life no longer followed the body, the landscape, or the course of the sun, but rather an abstract information system which we since then carry along in our pockets, on our wrists and screens.

From Solar to Standard

For centuries every town kept its own time. Noon arrived when the sun reached its highest point, whether in Paris, Warsaw, or Algiers. Because of the earth’s rotation, these local noons differed — a few minutes between London and Oxford, an hour between Paris and Warsaw ... Such differences mattered little in a world where movement was slow and distances vast.

The nineteenth century forced a reckoning. The Invention and growing implementation of railways and telegraphy compressed space and with it the tolerance for temporal difference. A train could not arrive at twelve o’clock in one city and depart at twelve o’clock in another unless those twelves were the same. Passengers needed synchronized timetables for travel planning, but asynchronous time was also dangerous for the railway companies themselves: trains running on different times increased the risk of colliding on shared tracks significantly.

Out of this friction came standard time. Britain’s railways began adopting Greenwich Mean Time in the 1840s, sometimes with two-hand clocks in stations: one hand for local time, one for Greenwich. Around 1855, nearly all public clocks in Britain pointed to Greenwich. In 1880, Parliament codified GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) as the nation’s legal time.

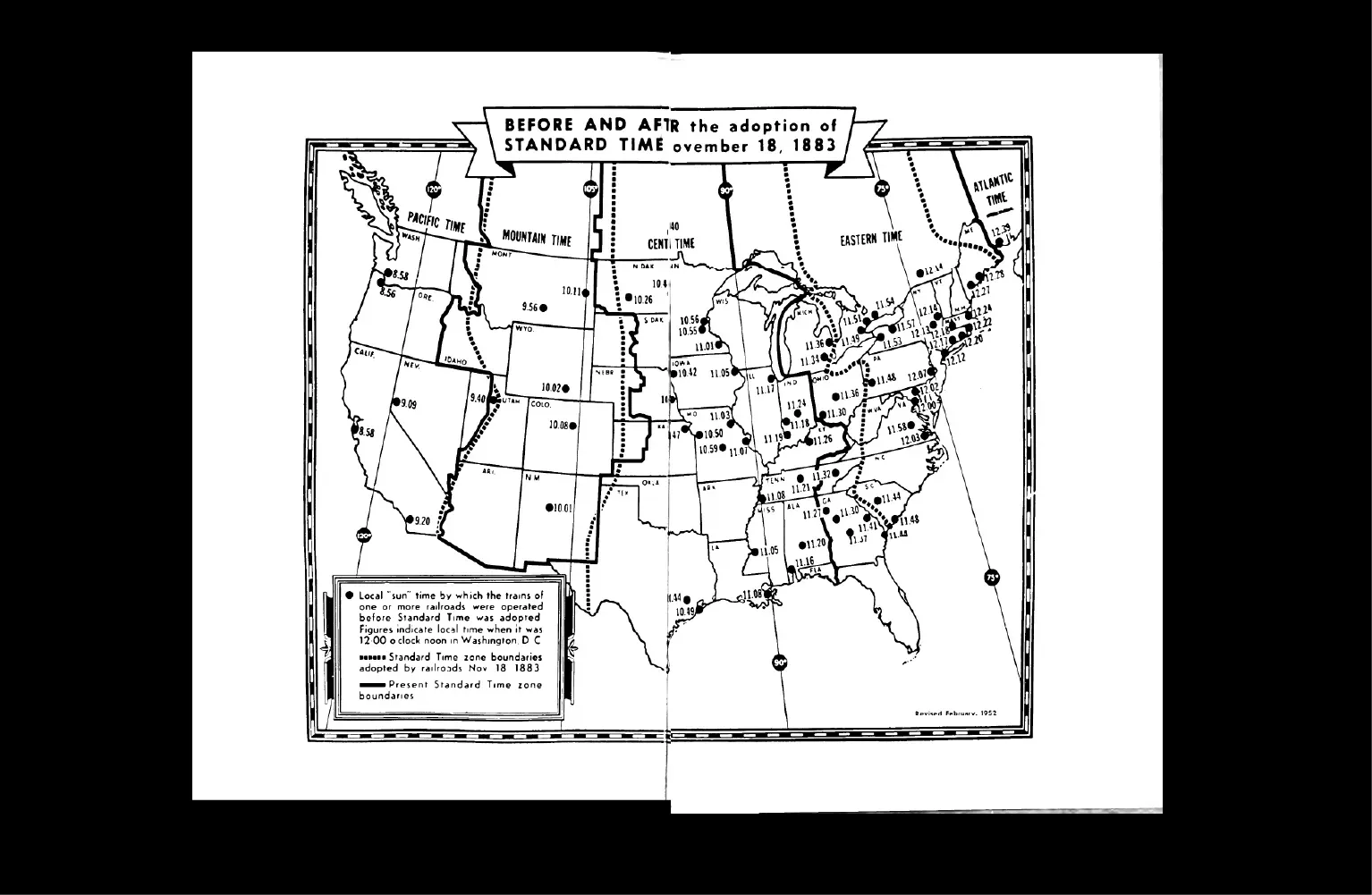

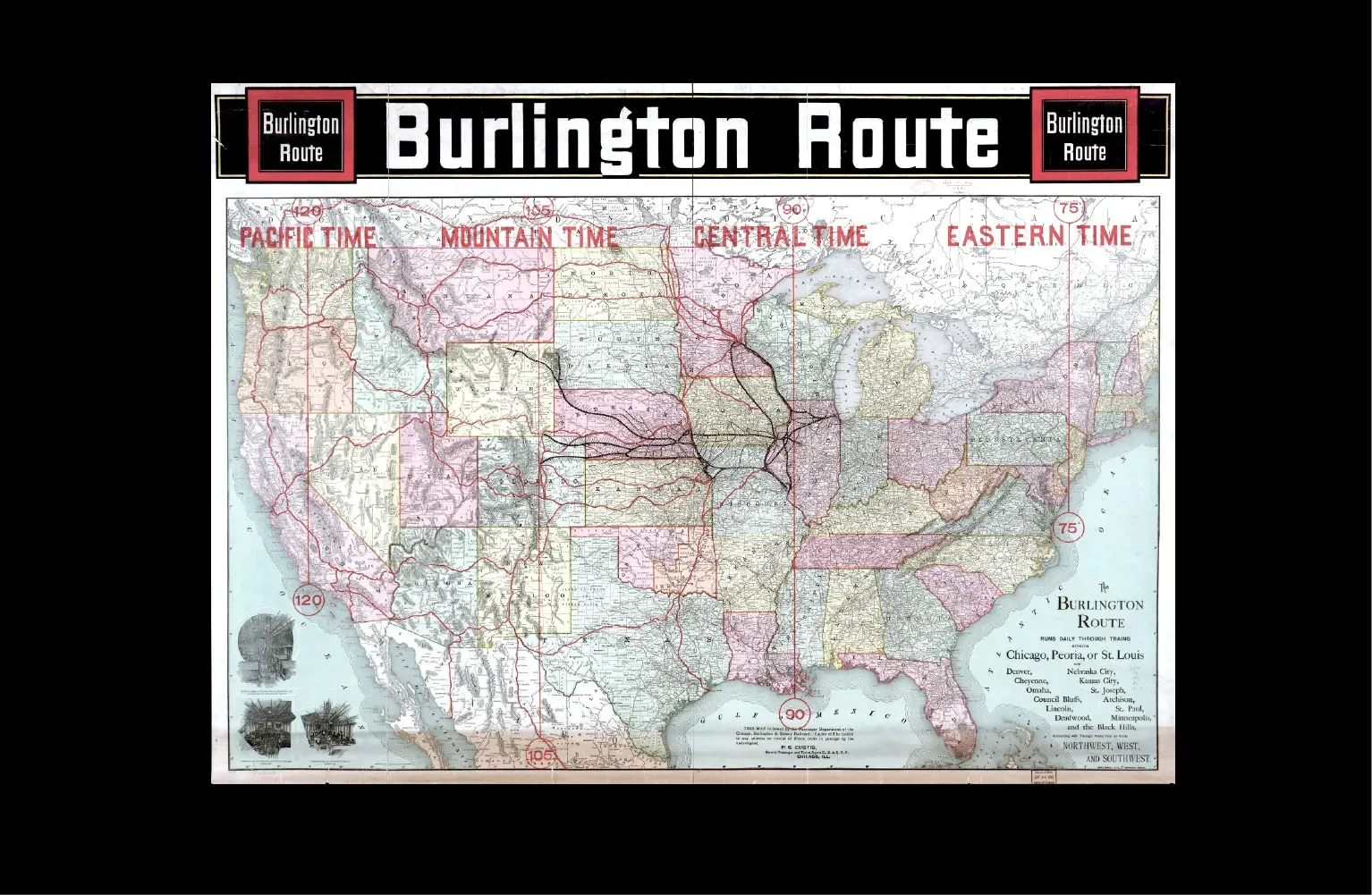

The United States followed with a more dramatic gesture. On 18 November 1883 — the Day of Two Noons — American railroads abolished dozens of local times and imposed four vast standard zones. Cities from Boston to Chicago shifted their clocks to align with the new grid.

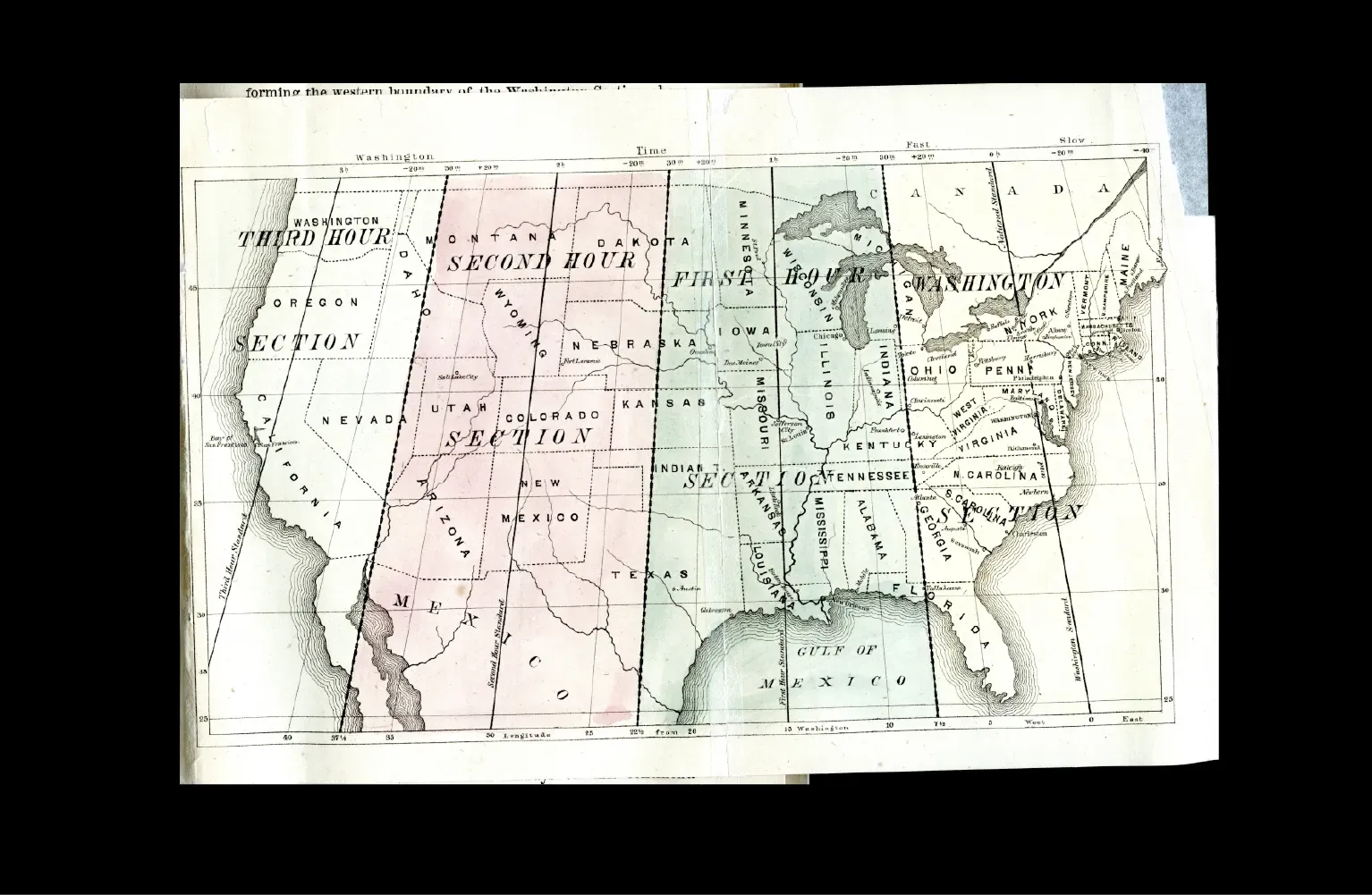

Left: Not realized Proposal from Charles F. Dowd for 4 Timezones in the USA, 1870 (Source). Right: Map of the USA showing realized Timezones and Railways, 1892 (Source).

A year later, the International Meridian Conference in Washington formalized Greenwich as the zero meridian. The planets time was hereby organized as twenty-four longitudinal slices, each fifteen degrees wide.

What had once been a slow drift of shadows across town squares was now abstracted into an universal information system of synchronization — and a cultural and political space of possibilities, both sovereign and imperial.

Timezones as cultural and political operations

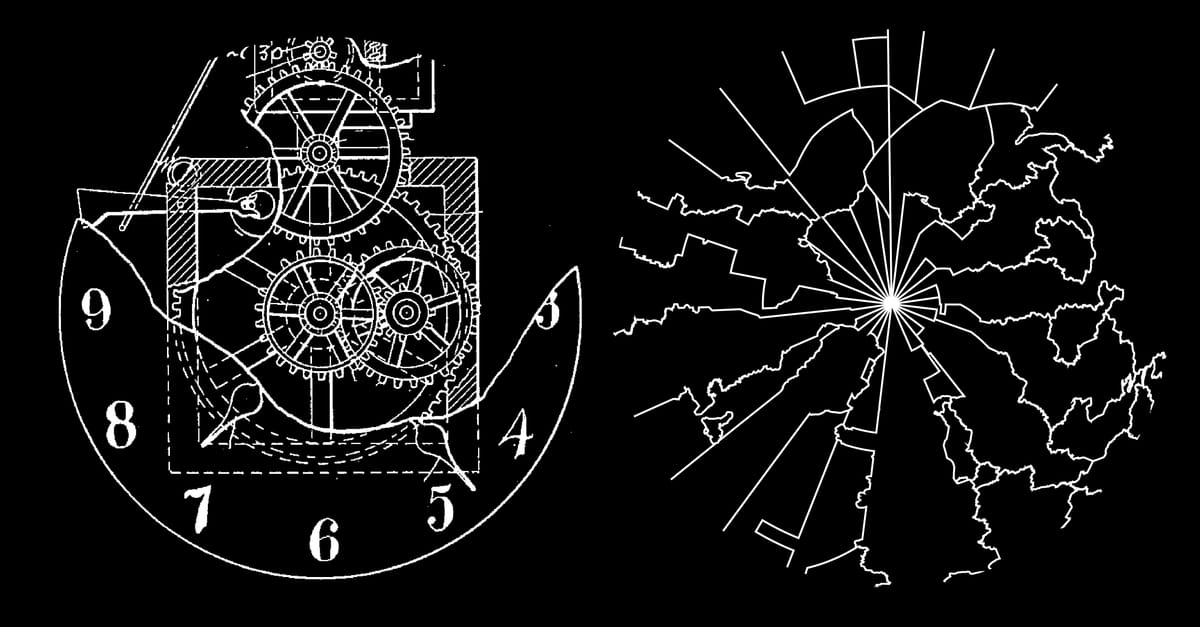

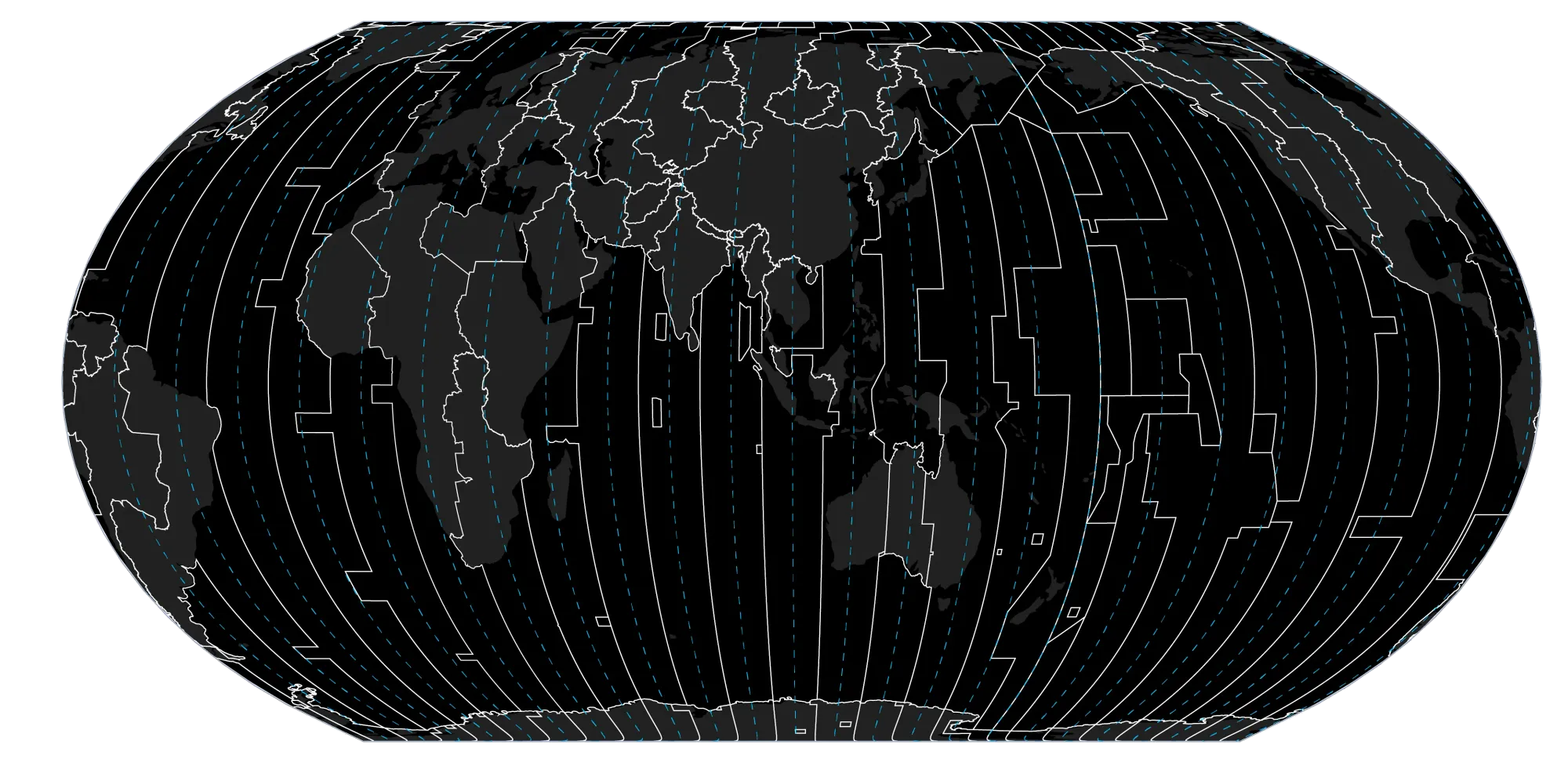

The ways in which time is bent by politics and culture become clearest when projecting the mean natural solar time (blue lines) and the political time zones (white lines) onto a map and compare them: Instead of neat divisions that follow the course of the sun, we find jagged rectangles cutting across oceans, abrupt turns around borders, and entire landmasses unified under one time.

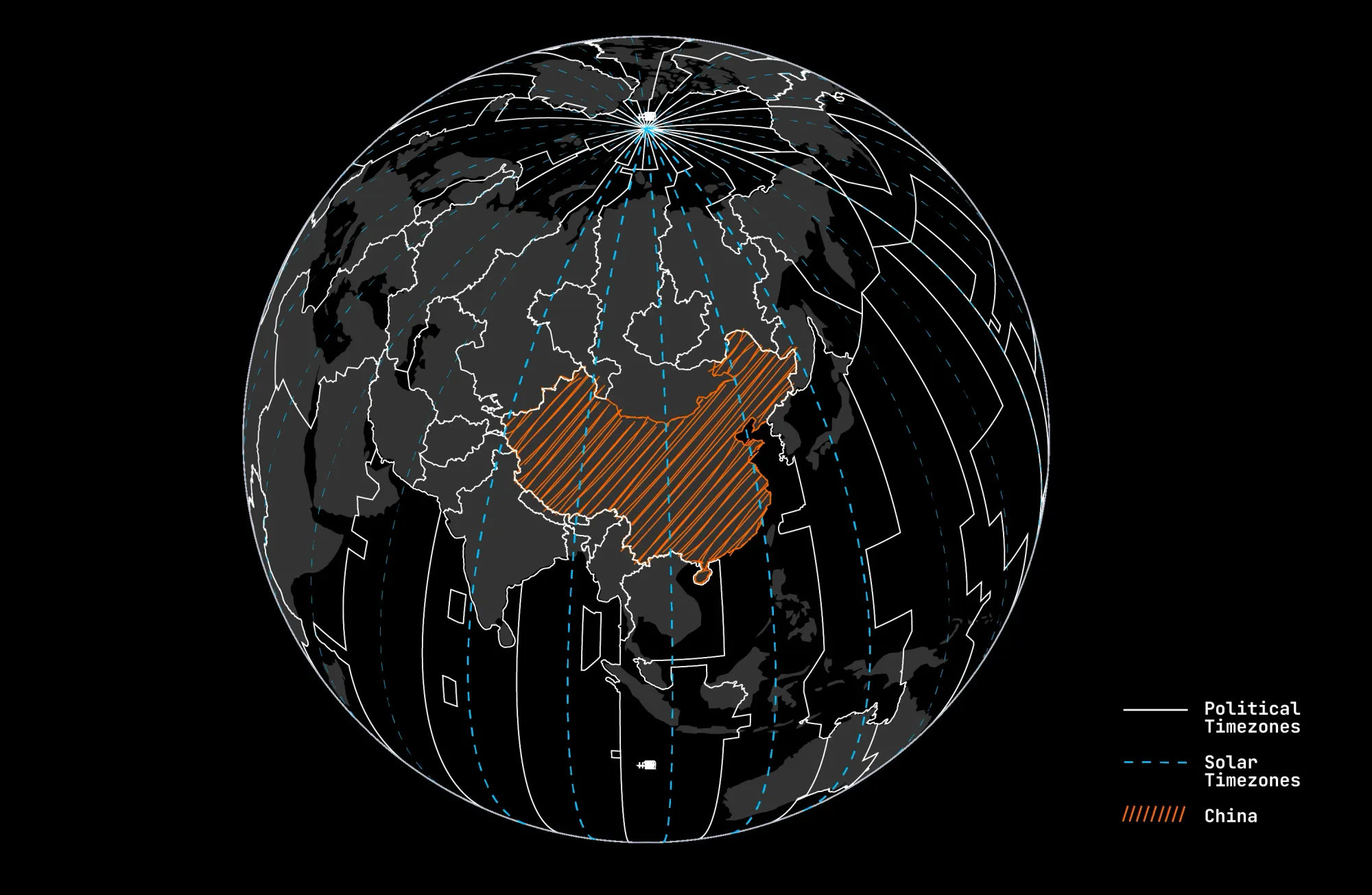

China’s One Timezone Politic

While studying the map, the eye almost automatically stops at China. A huge landmass that spans five mean solar zones (blue lines) — stretching from roughly the 75th to the 135th meridian — appears as a single block: Not a single political Timezone divides the landmass.

That is because since 1949, the entire nation runs on »Beijing Time«. In Kashgar, near the western edge, the sun rises close to 10 a.m. by the official clock. Markets open in darkness; children attend school long before dawn of sun. The uniformity of the timezone seems less about efficiency than about sovereignty: an informationsystem as both a symbolic and temporal projection of political unity across the country.

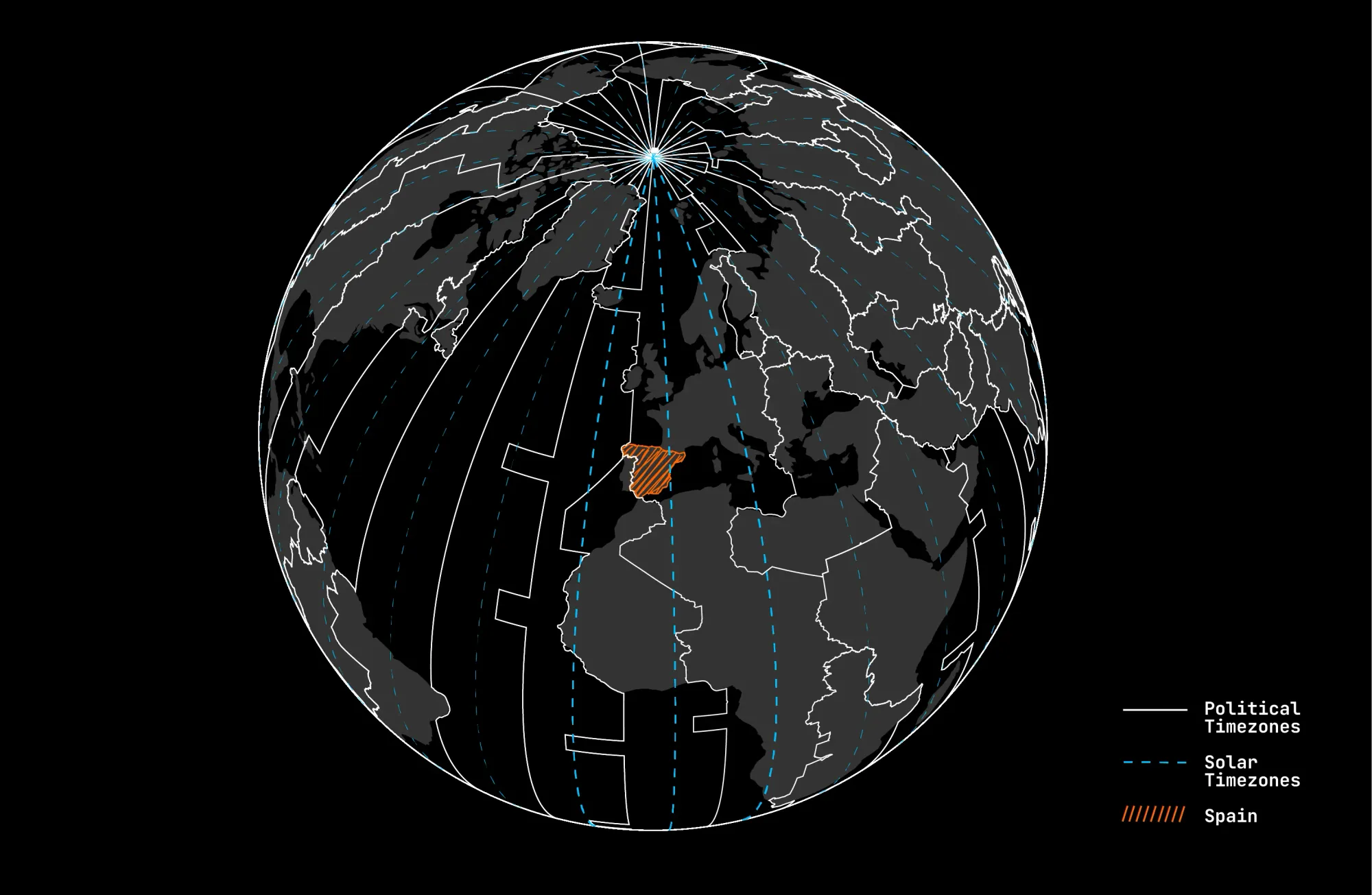

Franco’s Shadow in Spain

When inspecting the map further, it appears that Spain geographically belongs to Greenwich Mean Time, like Britain and Portugal (See the Blue Dashed Line in the Middle). Yet in 1940 the Spanish General and Dictator Franco, shifted the clock forward one hour to align with Nazi Germany — a wartime decree that outlasted the war itself. (Other occupied or allied countries, such as the Netherlands and France, also adjusted their clocks under, but most reverted after 1945.). Today the Nations is known to eat dinner very late. The visualization shows that this »late Spanish lifestyle« is not a sort of cultural custom but a political relic.

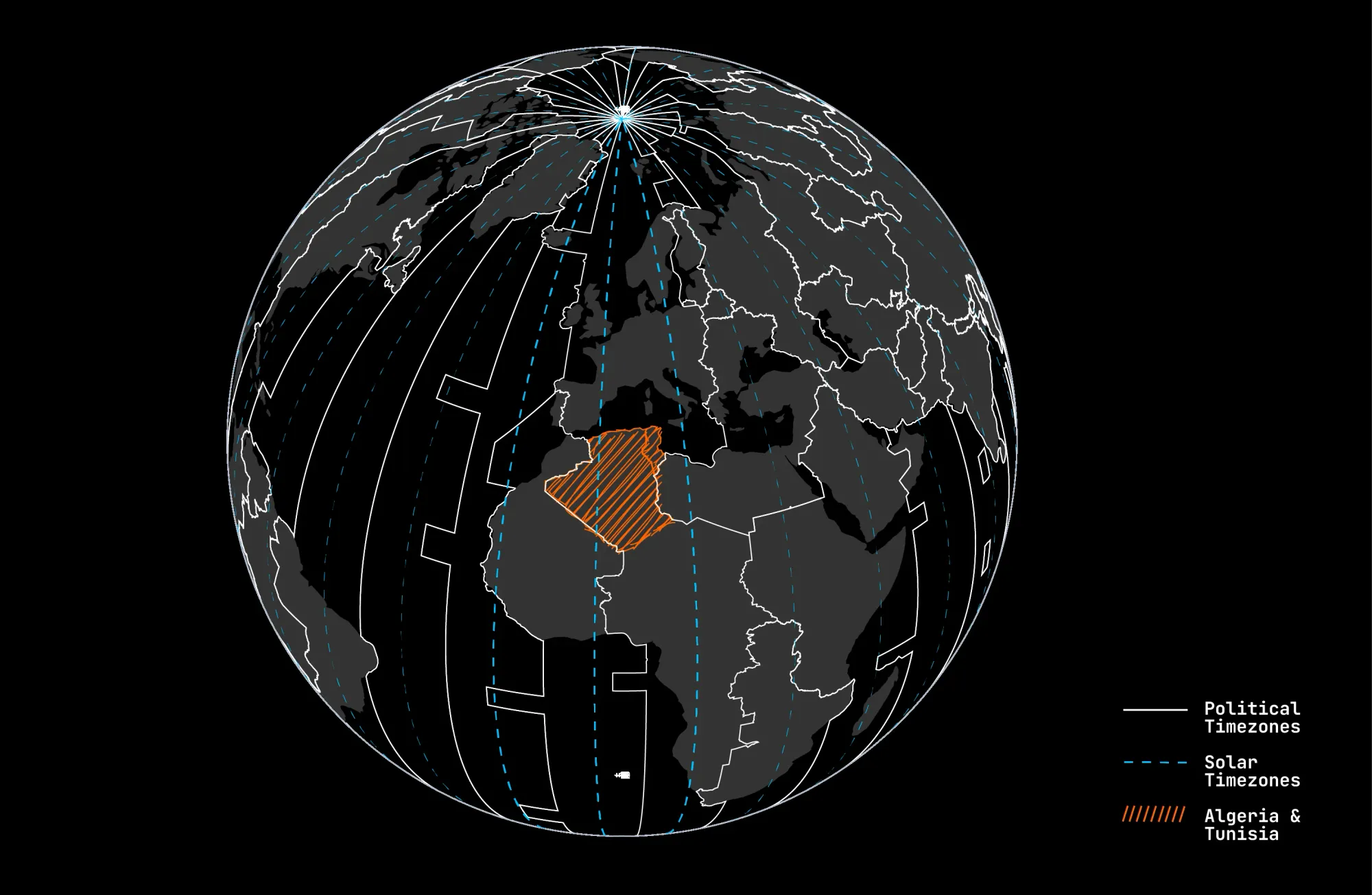

Algeria and Tunisias colonial Ghosts

Geographically, Algeria and Tunisia also fall within the Greenwich Mean Time solar zone, alongside Britain and Portugal. Yet under French colonial rule, both were aligned with Paris time — an artificial eastward shift that disregarded solar position. Unlike other regions that reverted after independence, Algeria and Tunisia maintained this inherited schedule. To this day, both countries remain on Central European Time, a lingering imprint of colonial administration.

Fifteen Minutes of Sovereignty between Nepal and India

Nepal adopted a time zone offset of +5:45 hours from Greenwich — fifteen minutes ahead of India. Officially, this choice aligns more closely with the country’s solar time, anchored near the Gauri Shankar mountain east of Kathmandu. Yet the unusual quarter-hour offset also carries symbolic weight: by setting its clocks apart from its powerful neighbor by the slimmest of margins, Nepal marked independence in minutes.

Such discrepancies reveal that our timezones –there are momentarily 41 different in effect– are less a reflection of natural cycles than a product of political and administrative decisions. Time zones function as instruments of governance, coordinating economic activity, regulating mobility, and symbolically asserting sovereignty. What appears as a technical informationsystem is in fact also a political and cultural infrastructure.